Bytes of History

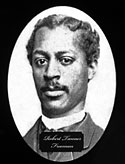

Robert Tanner Freeman

Robert Tanner Freeman was born in Washington DC in 1846. He was the son of slaves who had bought their freedom in the 19th century. Historical records are unclear but they probably adopted the surname Freeman in response to their transition.

Robert Tanner Freeman was born in Washington DC in 1846. He was the son of slaves who had bought their freedom in the 19th century. Historical records are unclear but they probably adopted the surname Freeman in response to their transition.

In those days many dentists learned their profession–really more properly thought of as a trade at that time–as apprentices and laboratorians. This preceptorial system was rightly criticized by those who believed that theory, as well as practice, was vital in the education of a dentist. The first three formal dental schools created in response to this need were the Baltimore College of Dental Surgery founded in 1840, the Ohio College of Dental Surgery founded in 1845, and the Michigan School of Dentistry. These were all stand-alone schools however–the medical schools and universities of the time refused to let dentistry become a part of their curriculum. They viewed dentistry as a trade rather than a profession requiring a university-based education. Yet it eventually became apparent that the public would best be served by making formal dental education part of the university system, on the same level as medical schools. The first university-based dental school in the United States was Harvard Dental School, founded in 1867. (The second was the University of Michigan in 1875 and the third was the University of Pennsylvania in 1878).

Robert Tanner Freeman had a strong interest in the health professions, and he sought work as a dental assistant and clerk from Dr. Henry Bliss Noble, his white dentist who tutored Robert and encouraged him to pursue his own career in dentistry. Dr. Noble hired Robert to work in his office which was in the 1500 block of Pennsylvania Avenue in Washington, DC. At this time it is estimated that there were a total of 120 African-American dentists in the entire U.S. All of those dentists had learned via informal apprenticeship.

Dr. Noble “was a reputable dentist whose humane acts of employment and encouragement of an African-American were indeed remarkable, especially in the nation’s capital where residents were sensitive to Confederate values and traditional interracial dogma,” wrote dental historian Dr. Clifton O. Dummett in Courage and Grace in Dentistry: The Noble, Freeman Connection, from the Journal of the Massachusetts Dental Society (1995).

Dr. Noble “encouraged him to think seriously about pursuing a dental career, pointing out that Freeman would be in a better position to help alleviate human suffering and serve the dental health needs of his fellow African-Americans in this way.”

Thus inspired, Robert applied to two of the independent dental schools. He was rejected on racial grounds.

Then, Dr. Noble set about the process of working his colleagues.

Noble was well acquainted with Dr. Nathan C. Keep, Harvard Dental School’s first Dean, and other members of the Board of Trustees. Dr. Noble strongly lobbied these men to accept his African-American employee and friend into the first class of their new school. At first there was resistance, and they too considered rejecting Robert’s application. As they met, however, the conversation must have taken an unexpected course, as it often does in a new, creative grouping of people. These academics were, after all, taking what was a trade and molding it into an integral part of the medical profession. On Dr. Keep’s recommendation, Harvard decided the school would “know no distinction of nativity or color in admitting students.” They also stated that they wished to establish a tradition of inclusion, not exclusion, as they began their enterprise. Dean Henry M. S. Miner later wrote: “Robert Tanner Freeman, a colored man who has been rejected by two other dental schools because of his race, was another successful candidate. The dental faculty maintained that right and justice should be placed above expediency and insisted that intolerance must not be permitted.” Dr. Freeman thus became the first African-American graduate of a U.S. dental school in history.

After graduating from Harvard in 1869, Dr. Freeman returned to Washington, D.C., and practiced in the same building as his mentor, Dr. Noble. Unfortunately, his death came only four years after dental school. He contracted one of the water-borne diseases so common at that time, most probably cholera. Every indication is that he served his community in an exemplary way and gave vital assistance to an African-American community in a time of tremendous cultural and political change. Recall that the American Civil War had only ended 4 years before his graduation.

His career also began a distinguished legacy for his family. Dr. Freeman’s grandson, Robert C. Weaver, Ph.D., became the country’s first African-American presidential cabinet member, serving as Lyndon B. Johnson’s Secretary of Housing and Urban Development.

None of this success would have happened without a small group of dentists listening to a few influential members who stood up for something that must have been exceedingly unpopular at the time. I also find it interesting and inspiring that the decisions of a relatively small circle of people in the 1860s could reverberate down through time into the 1960s and influence choice at the presidential cabinet level. Dr. Weaver would not have been able to reach his own success without building on that of his grandfather.

Rick Wilson, D.M.D.

Gabriel d’Erchigny de Clieu

We’ll return to dental history in the next installment of Bytes of History; for now let�s appeal to the coffee (and tea!) drinkers in the audience!

We’ll return to dental history in the next installment of Bytes of History; for now let�s appeal to the coffee (and tea!) drinkers in the audience!

For most cultures in most of human history, no adult was ever completely sober.

That’s right. You didn’t think they drank water, did you? Water was always suspect. Without modern sanitation facilities there was always the risk of water-borne diseases: cholera, typhoid, dysentery. Some have called these diseases the biggest killers of all time. So if not water, then what? Depending on the culture, they drank beer or wine. The process of fermentation did away with much risk. Most people in most places, since the dawn of agriculture, did not drink plain water. They went through their lives in a constant state of mild inebriation.

Coffee, tea, and hot chocolate were available in some parts of the world (depending on how strictly the Islamic prohibition against alcohol was enforced). Nowadays, each has a staunch following of devotees. But until the 1600s, coffee, tea and chocolate — the only plant sources of caffeine edible by human beings — were completely unknown in Europe and the Americas. Even after Pope Clement the VIII proclaimed that it would be “a shameful waste” to leave the enjoyment of coffee to the heathen, officially sanctioning it to the vast, influential Catholic Church, one nation — the Dutch — exclusively controlled its production. Prices were very high, and supplies were limited. Simply put, there were no competitors.

This is the story of the man who changed all that.

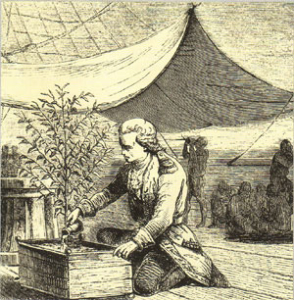

Gabriel d’Erchigny de Clieu was a French naval officer and resident of Martinique, in the Caribbean. De Clieu had a secret ambition: to steal a coffee plant from the Jardin des Plantes, where Louis XIV had them jealously protected. De Clieu’s plan was to cultivate coffee plants in the West Indies, but getting such a plant was an incredible challenge. The plants were guarded with great zeal.

De Clieu’s solution was a lateral attack. He persuaded a young lady of the Court to prevail upon M. de Chirac, the Royal Physician, to purloin one of the rare plants from the Jardin. And in 1723, de Clieu sailed from Nantes with his single, precious coffee plant installed in a glass-framed box on the deck of the ship — a sort of protective greenhouse.

His crossing was difficult. A Dutch-speaking passenger (perhaps an early example of an industrial spy!) seemed intent on disrupting de Clieu’s plans; on one occasion de Clieu surprised him in the act of opening the greenhouse and snapping off a twig. But that wasn’t all — the ship barely escaped an attack by Tunisian pirates, and heavy storms nearly smashed the greenhouse. The greatest threat, during a prolonged calm, was the rapid depletion of drinking water aboard ship. De Clieu wrote:

“Water was lacking to such an extent that for more than a month I was obliged to share the scanty ration of it assigned to me with my coffee plant, upon which my happiest hopes were founded and which was the source of my delight.”

Despite all, de Clieu did make it home to Martinique, coffee plant intact! He set it out with great care, under guard. Upon reaching maturity it bore coffee beans, and propagated with ease in the friendly climate. Eventually coffee plantations sprang up all over South America, particularly Brazil. Many botanists feel that the entire population of coffee plantations in the New World, until recent mixing, descended from De Clieu’s single enterprising plant.

By 1746, with lower coffee prices and greater cultural acceptance, de Clieu was presented before Louis XV, who (unlike his father) was a serious coffee drinker! De Clieu was appointed Governor of Martinique, an honor bestowed for his cultivation of coffee.

The shift from wine and beer (which dull the senses) to coffee and tea (containing stimulants) was world-changing. Along with railroads and the telegraph, the partial replacement of alcohol with caffeine as the most commonly used drug in the world encouraged modern work methods and industrial progress. Thanks to the vision and perseverance of one man willing to challenge the status quo, the coffee drinker’s barrier to entry was altered dramatically: from wealth and influence to simple taste.

Rick Wilson, D.M.D.

Anesthesia: Dentistry’s Great Contribution to Medicine

Anesthesia. The ability to block painful sensations during surgical procedures of any kind. Of all our advancements in medical knowledge, it can be said that no other has alleviated human suffering more than the discovery of anesthetics.

Anesthesia. The ability to block painful sensations during surgical procedures of any kind. Of all our advancements in medical knowledge, it can be said that no other has alleviated human suffering more than the discovery of anesthetics.

This great gift to Mankind was made by an American dentist in 1844.

Well, sort of. It’s complicated…

In the last quarter of the eighteenth century, chemists, especially in England, were discovering and isolating gases, such as oxygen and nitrogen. Joseph Priestly discovered nitrous oxide in 1772, as well as oxygen in 1774. Oxygen was isolated by Daniel Rutherford in 1772. The medical establishment at the time had high hopes for using these newly revealed substances to cure various illnesses; a number of “Pneumatic Institutions” were established where gases were administered to patients suffering from a range of diseases.

It wasn’t in a medical institution where the ability of these agents to block painful sensations was first noticed, however. In America there were many itinerant showmen who styled themselves “professors” and traveled about holding popular demonstrations of the effects, among other things, of nitrous oxide. “Professor” Gardner Quincy Colton was one of them. Keep in mind that nitrous oxide’s effects vary according to the situation, and although most people remain quiet and relaxed during dental treatment, when an audience member volunteers to go on stage they tend to get much more excitable, similar to the experience of having a few drinks and then taking the microphone and singing karaoke.

Well, on December 11, 1844, Dr. Horace Wells, a young dentist from Hartford, Connecticut, attended one of the Professor’s exhibitions. An acquaintance of Well’s, a fairly large man named Cooley, volunteered, breathed the requisite nitrous oxide, and was dancing around the stage when he fell off the edge and severely scraped his shin. He returned to his seat and for a few minutes seemed to have absolutely no awareness of any pain. History has not recorded for us his reaction when the nitrous wore off and he felt the full force of his injury, but we do know that Wells immediately saw the implications of this event. In his mind, there was tremendous potential in nitrous oxide to alleviate the suffering that patients experienced during tooth extractions.

Wells happened to need a molar tooth extracted himself. He asked Professor Colton to come by his office the next day with a supply of nitrous oxide. Colton administered the gas to Wells and Well’s colleague, Dr. John Riggs, extracted the tooth. Wells’ exact words upon awakening were: “I didn’t feel it so much as the prick of a pin. A new era in tooth-pulling has arrived!”

(I have to note here that at that time, unlike today, the nitrous oxide was used at 100% concentration, giving almost full anesthesia- but no oxygen! Machines today cannot exceed 70% nitrous oxide/ 30% oxygen; patients are always getting more oxygen than there is in the air around us, which is 21%. The fact is, back in the 1800’s one was either alive and well or- not!- so that techniques like this, risky by today’s standards, tended to have relatively few complications, as the patients were fairly robust to begin with.)

The next step for Wells was to petition the prestigious Massachusetts General Hospital for the chance to demonstrate his discovery. In January 1845 he presented himself at Dr. John Collins Warren’s class and extracted a tooth for one of the students. Wells withdrew the gas a bit early and the student briefly cried out in pain, yet afterward insisted that he had felt nothing. He probably didn’t remember coming out of the anesthesia. Unfortunately, Wells was hissed and booed out of the class. Not one to be put off easily, Wells continued to use nitrous oxide for extractions in his dental practice, and he discussed his work with another colleague and former student, Dr. William Thomas Greene Morton.

Morton talked about nitrous oxide with one of his professors, Charles Jackson. Jackson had the habit of inhaling ether, and often fell unconscious. Morton tried ether himself and then, on September 30, 1846, performed his first extraction where the patient inhaled ether. This was also a success, the patient having no sensation of pain during the extraction.

It was now Morton’s turn to ask Dr. Warren for a chance at a demonstration of anesthesia during surgery. We can only imagine the good surgeon’s reaction at being pestered by so many dentists to try something so radical at the time as anesthesia! However on October 16, 1846, Morton administered ether to a surgical patient and Warren removed a tumor from the neck of his patient, Gilbert Abbott. It is also difficult for us to imagine today the advantages to a 19th century surgeon of not having their patient screaming and moving due to the pain of a procedure, but Dr. Warren must have been thrilled and impressed because he turned to his audience of students and exclaimed, “Gentlemen, this is no humbug!” (Slang evolves, but a humbug was a very very bad thing in the 1800’s.)

The concept of using anesthesia during surgery and dental procedures spread swiftly around the world and met with rapid acceptance once influential surgeons started to operate routinely with its benefits.

As usual in the course of human affairs, once an enormous sum of money enters the picture, things start to get complicated. The U.S. Congress voted to award an honorarium of $10,000 to the discoverer of anesthesia. Wells, Morton, and Jackson all applied, as did Georgia physician Dr. Crawford Long. Long claimed to have used ether anesthesia since 1842 and produced affidavits to this effect from some of his patients, but his position was weakened somewhat by the fact that he had never spoken, lectured or written on the subject before any medical group. Then there is this excerpt from a letter that Long wrote to his friend Robert Goodman:

“I am under the necessity of troubling you a little. I am entirely out of ether and wish some by tomorrow night� We have some girls in Jefferson who are anxious to see it taken, and you know nothing would afford more pleasure than to take it in their presence and to get a few sweet kisses…”

Not exactly following modern ethical principles in medicine, was he?

The controversy surrounding the discoverer of anesthesia ran on for so long that Congress finally withdrew its offer. The lives of these four men who contributed so much to humanity did not end so well:

-Wells became obsessed with obtaining the recognition due him and became addicted to chloroform. He committed suicide in jail at the age of 34.

-Morton became very poor due to his legal fees, incurred in fighting for a share of the profits from what he considered his invention. He died a pauper at age 49.

-Jackson was committed to a mental institution.

-Long went back to his small-town medical practice.

Who most deserves the credit for discovering anesthesia, and giving the world relief from the pain of all kinds of surgical procedures? In terms of both awareness of the significance of what they saw, and of communicating their discovery to others in the medical field, Dr. Horace Wells would seem to be the best candidate for this honor. Both the American Dental Association, in 1864, and the American Medical Association, in 1870, resolved that “The honor of the discovery of practical anesthesia is due to the late Dr. Horace Wells of Connecticut.”

Rick Wilson, D.M.D.

Dr. Lucy Hobbs Taylor

It is extremely difficult for young women today to envision how difficult it was for a woman in the 19th century to advance along a fulfilling career path. Even in the first half of the 20th century countless women were told by their parents that “there’s no need for girls to go to college”. And yet just as with all other forms of prejudice or elitism, there were always outliers, defined by Malcolm Gladwell as “people who do not fit into our normal understanding of achievement”. Here, then, is the story of a very persistent and brilliant outlier, Dr. Lucy Hobbs Taylor, the first female dentist in the United States.

It is extremely difficult for young women today to envision how difficult it was for a woman in the 19th century to advance along a fulfilling career path. Even in the first half of the 20th century countless women were told by their parents that “there’s no need for girls to go to college”. And yet just as with all other forms of prejudice or elitism, there were always outliers, defined by Malcolm Gladwell as “people who do not fit into our normal understanding of achievement”. Here, then, is the story of a very persistent and brilliant outlier, Dr. Lucy Hobbs Taylor, the first female dentist in the United States.

Born in Constable, N.Y. in 1833, Lucy had a strong interest in health care from a very young age. She started out teaching school in Michigan. In 1859 she moved to Cincinnati and applied to the interestingly-named Eclectic College of Medicine. In spite of the name hinting at diversity in the student body, Lucy’s application was rejected because of her sex.

A determined young woman, Lucy found a lateral solution to this challenge and studied privately with one of the school’s professors, who steered her towards dentistry. She next applied for admission to the Ohio College of Dental Surgery and was again rejected because of being female. She again thought not only outside the box, but outside the room which contains the box, and was able to persuade the college dean to tutor her privately.

Finally, in 1861, the now 28-year-old Lucy opened a dental practice in Cincinnati and later moved her practice to Iowa. There, a few years later, the Iowa State Dental Society accepted her as a member. Now, here’s the thing about outliers- they don’t just get a foothold in the realms denied to them and then rest on their laurels. No, outliers can most often be counted on to keep achieving way beyond what’s nominally expected of them. So, our Lucy was sent by the Iowa State Dental Society as a delegate to the ADA’s 1865 convention in Chicago.

In those days apprenticeships vied with formal dental school training as a way into the profession, but a degree always conferred higher status and was becoming more of a prerequisite for success all the time. So, with her Iowa accomplishments set to impress, Lucy was finally accepted into that same Ohio College of Dental Surgery as a member of its senior class in 1865. Receiving credit for her years as a practicing dentist, Lucy earned her DDS degree in February 1866. She thus became the first woman in the world to hold a formal degree in dentistry. (Note the close proximity to Dr. Freeman’s graduation from Harvard- 1869.)

Perhaps the most charming part of the story is what came next. In 1867 Lucy married Civil War veteran James M. Taylor, who became a dentist under his wife’s guidance!

The couple moved to Lawrence, Kansas, where they managed a large and successful dental practice. “Dr. Lucy”, as she was known to her patients, died in Lawrence on Oct. 3, 1910 at the age of 77.

There’s more here:

http://home.comcast.net/~thorsdag/LucyHobbsTaylor.html

Dr. Lucy remains one of this author’s favorite outliers- ever.

Rick Wilson, D.M.D.

Alice Hamilton, M.D.

I am fascinated by outliers.

In mathematics, an outlier is defined as “a value that ‘lies outside’ (is much smaller or larger than) most of the other values in a set of data.”

When it comes to applying this delightful word to human beings, I find the Cambridge Dictionary definition to be the best: “a person, thing, or fact that is very different from other people, things, or facts, so that it cannot be used to draw general conclusions.”

Alice Hamilton, M.D. is my favorite American outlier, and one of my very favorite Americans ever.

Alice Hamilton was born on February 27, 1869, in Manhattan. Raised in Fort Wayne, Indiana, she was the second eldest of five children. Sisters Edith and Margaret became scholars and educators; Nora, an artist. Her brother Arthur also became an educator. He was also the only sibling to marry; he and his wife Mary had no children.

In their youth, the Hamilton girls attended Miss Porter’s Finishing School for Young Ladies in Farmington, Connecticut, which still exists today, albeit in an evolved form. Education was of paramount importance in the extended Hamilton family. Edith once described their father thus: “My father was well-to-do, but he wasn’t interested in making money; he was interested in making people use their minds.”

After a year of studying science back in Fort Wayne, Alice enrolled in the University of Michigan Medical School in 1892. It was certainly no easy task for a woman to gain acceptance to medical school in those days. Yet even in 1892, there were precedents. Here, from the University of Michigan website, we learn of its very first female graduate:

Dr. Amanda Sanford was the first woman to earn a M.D. degree from the University of Michigan Medical School, graduating with highest honors in her class in March 1871. Her graduation thesis, “Puerperal Eclampsia,” was a thorough review of the state of knowledge at the time about this dire obstetrical complication and included some original research as well as statistics and case studies. Former faculty member Henry F. Lyster, addressing the graduating class, honored her by saying, “It is my pleasing duty to welcome to the profession a woman coming from these halls.” Some young men threw paper at her from the gallery during Lyster’s address, but she maintained her composure and became even more determined in the cause of women’s rights.

After earning her medical degree in 1893, Alice and her sister Edith traveled to Germany to further their studies, Alice in bacteriology and pathology.

In 1897 Alice moved to Chicago, accepting an offer to become a professor of pathology at the Woman’s Medical School of Northwestern University. She became a resident and member of Hull House, the Settlement House founded by social reformer Jane Addams. (The Settlement Movement was a social movement that aimed to bring the rich and the poor of society together in both the physical and social senses; the goal was to transfer knowledge and life skills to the poor, and thus alleviate poverty.)

In her work with the working poor of Chicago, many of whom were immigrants, Alice came to define the “dangerous trades” as those which exposed workers to specific occupational diseases, diseases that could not be explained by factors outside the workplace. Lead poisoning was one of the greatest problems she identified; lead was used in the manufacture of thousands of items, from paint to bathtub enamel to solder to early batteries. At the time, industrial medicine was not being much studied in America. Alice contributed her first of many scientific papers to this discipline in 1908.

In 1910, Illinois governor Charles S. Deneen appointed Alice as a medical investigator to the newly-formed Illinois Commission on Occupational Diseases. In time, this Commission’s report, the “Illinois Survey,” authored by Dr. Hamilton, led to the passage of the nation’s first worker’s compensation laws and occupational safety laws in Illinois in 1911.

Dr. Hamilton was by now recognized as America’s leading authority on lead poisoning. In 1919, she was hired by the Harvard Medical School in the newly-formed Department of Industrial Medicine. Though her title was assistant professor, the Department was essentially founded around her. Yet at Dr. Hamilton’s request, this was a one semester per year appointment, which allowed her to continue her work for government agencies, and to continue to live at Hull House for half of each year. Throughout the 1910s and 1920s she investigated a wide array of occupational safety problems for various state and federal health committees. She described her work as “shoe leather epidemiology,” in which she combined personal visits to factories, interviews with managers and workers, and rigorous analyses of medical histories and case studies of diseased workers. Her efforts—rigorous, scientific and persuasive—influenced reforms and helped to bring about major gains in worker safely legislation and infrastructure, both local and nationwide.

The most remarkable thing about all the positive change Alice Hamilton created is that in no case did she have any actual authority to do anything. She served on government committees, but no powers of enforcement of any laws were given to her by any government, state or federal.

How, then, could she possibly be so effective, when the industrialists who ran things could simply ignore her at will?

Ah, this is where the core of Alice Hamilton’s outlier abilities came into play. Seen through the hazy distance of so many years, in an era long before conversations and meetings were commonly recorded in sight and sound, we cannot know with precision what it was like to engage Dr. Alice Hamilton in a one-on-one conversation—much less an adversarial one. Yet we are graced with her own words, as we are fortunate that she wrote a memoir in 1943. Let us then turn to those words and see if we can glean insights into how she wielded so much influence.

“Our procedure in the Illinois survey and in the work that I carried on later for the Federal government was completely informal. We had no authority to enter any plant, we had no instructions as to which we should visit, we simply explored the state. When we found a place which seemed to belong to our field, we asked permission to enter it. Never were we refused, never did I, at least, meet with anything but courtesy in those very early days. Sometimes it was because the manager was proud of his plant and eager to show it (even when it was outrageously bad); sometimes it was because he had a strong suspicion that all was not well with his men and he really wanted more light. As to the way we should deal with the conditions we found, that was a question for each of us to settle. The Illinois Commission expected me to report back to it and in such a way that no factory described in the report could be identified. That I did, of course, but I could not feel that my whole responsibility was thereby discharged. I was the only one who had seen the men working on the Scotch hearths in the smelters, emptying the baghouse and flues, sandpapering the lead-painted ceilings of Pullman cars, shoveling the white lead from the drying pans. How could I hope that a cold, printed report which would satisfy the Commission would serve to do away with these pressing dangers? There was no use in going to the factory inspectors: they were ignorant and powerless.

So, from the first, I made it a rule to try to bring before the responsible man at the top the dangers I had discovered at his plant and to persuade him to take the simple steps which even I, with no engineering knowledge, could see were needed. As I look back on it now from this changed world of “safety first,” expert factory inspection, the National Safety Council, industrial insurance companies, strict compensation laws, it astonishes and amuses me to see how very well this primitive method often worked.”

Here is one example—one excellent example of how Dr. Alice Hamilton worked her persuasive magic.

“Even more important reforms followed my contact with the National Lead Company which had several white-lead and lead-oxide works in and near Chicago. I visited them and found much dangerous work going on in all of them. One of the vice-presidents, Edward Cornish, later president, came to Chicago and I went to see him in the Sangamon Street Works. He was both indignant and incredulous when I told him I was sure men were being poisoned in those plants. He had never heard of such a thing; it could not be true; they were model plants. He went to the door and shouted to a passing workman to come in. ‘Did the lead ever make you sick?’ he demanded. The man, a badly scared Slav, stammered, ‘No, no, never sick.’ ‘Any other men sick?’ demanded Mr. Cornish. ‘No, no, all good,’ and the poor man escaped quickly. ‘There,’ said Mr. Cornish, ‘you see!’

‘But I do not see,’ I answered. ‘Your men are breathing white-lead dust and red lead and litharge and the fumes from the oxide furnaces. They are no different from other men; a poison is a poison to them as it is to any man.’

He thought a moment and then he said, ‘Now, see here. I don’t believe you are right, but I can see you do. Very well then, it is up to you to convince me. Come back here with proof that my men are being poisoned and I give you my word that I will follow all your directions, even to employing plant doctors.’

It was not an easy task I faced, tracking down actual, proved cases of lead poisoning among men who came from the Serbian, Bulgarian, and Polish sections of West and Northwest Chicago, and were known to the employing office only as Joe, Jim, or Charlie, with no record of their street and number! It meant digging up hospital records, for I had to be sure of the diagnosis, then a search for the home, and finally an interview with the wife to discover where the man had been working, for of course no hospital intern ever noted where the victim of plumbism had acquired the lead. Hospital history sheets noted carefully all the facts about tobacco, alcohol, and even coffee consumed by the leaded man, though obviously he was not suffering from those poisons; but curiosity as to how he became poisoned with lead was not in the intern’s mental make-up.

In the end I was able to present Mr. Cornish with authentic records of twenty-two cases of plumbism severe enough to require hospital care. He was better than his word. Beginning with the Sangamon Street works, he went on to reform all the plants in the Chicago region, and this meant dust and fume prevention, often by methods which had never before been worked out. There were no models to follow; the engineers faced new problems. As each was solved, Mr. Cornish sent the blueprints to the plants in other states and later on, when I visited these, invariably I found the same changes being introduced. I had told Mr. Cornish he could never fully protect his men unless he employed doctors to keep strict watch over their condition, to make at least a brief inspection of each lead worker once a week. He accepted this recommendation without protest and before our report was published there was a medical department in each plant of the National Lead Company in Illinois.

I have met many admirable men in industry throughout these thirty-two years, but my warmest gratitude and admiration goes to Edward Cornish.”

Such were the powers of human connection wielded by Dr. Alice Hamilton.

Perhaps the only significant harm inflicted by industrialists upon the American population that Dr. Hamilton could not prevent was that of leaded gasoline.

In the 1920s, automobile manufacturers were increasing the compression ratios in their gasoline-powered internal combustion engines, for two reasons: to increase fuel mileage, and to increase horsepower. The problem with this was engine knocking. Knocking means loud explosions inside the engine that frightened motorists and pedestrians and damaged the internal workings of the engines themselves.

Alfred Sloan was the President, Chairman and CEO of GM in those days. Engineer Charles Kettering was head of research at GM from 1920 to 1947. Kettering was the inventor of the electric starting motor and many other innovations that were key to the development of the automobile. Striving to solve the problem of engine knocking, Kettering assigned engineer Thomas Midgley to find an anti-knocking solution. They gave him a one-cylinder lab engine and let him try whatever he might.

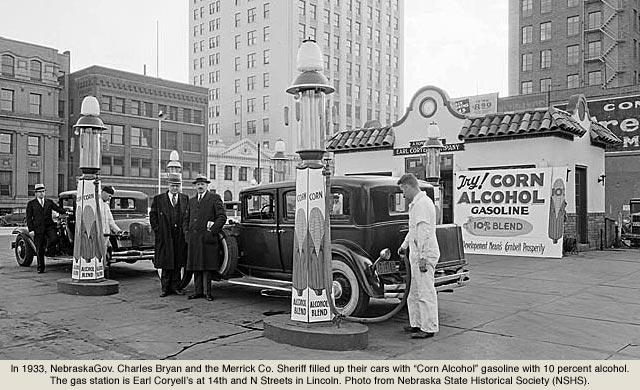

Midgley first found that ethanol never knocked, even at high compression ratios. This was not an acceptable solution for two reasons: America did not have a sufficient ethanol producing infrastructure at that time, and using ethanol as fuel would have angered the main supplier of fuel for GM cars, Standard Oil.

Midgley then found that 10 % ethanol (much as we employ today) mixed with 90% gasoline would stop knocking just fine. The problem with this solution is that anyone could do it: there was nothing to patent that would stand to make GM a separate set of profits outside of what it was making from the production of automobiles.

What happened next leaves the realm of science and borders on farce. Midgley started adding chemicals at random to the gasoline he fed into his one-cylinder lab engine. He tried this and that, organics and inorganics, large molecules and small, until one day he laced his gasoline with highly poisonous tetraethyl lead. Lead itself is the most poisonous non-radioactive element. In its tetraethyl form it is exceedingly dangerous. And yet a triumvirate of General Motors, Standard Oil and DuPont set out to manufacture gasoline laced with tetraethyl lead, marketed as “Ethyl” in order to avoid any negative connotations associated with the other word that should have made up its name.

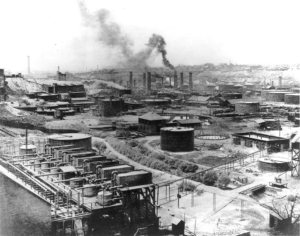

At least 17 workers died in the early days of Ethyl’s manufacture, and many others were severely injured, in Standard Oil and DuPont refineries in Bayway and Deepwater, New Jersey. And yet the worst of it was the perfect mechanism that Sloan, Kettering and Midgley had devised for spreading one of the worst toxins known into Earth’s entire biosphere: the automobile tailpipe.

By 1929, there were 26 million gasoline-powered vehicles in the United States, 23 million of them passenger cars. Of course, this number would only grow. In the mid-1980s, when leaded gasoline was finally phased out, there were nearly 200 million gasoline-powered vehicles on American roads. From 1921 to the end of 1986, when leaded gasoline was largely phased out, all those millions of tailpipes provided a highly efficient distribution system for lead to be placed—irreversibly—into our environment.

At the 1925 Public Health Service conference on the use of lead in gasoline, Dr. Hamilton and others testified against this use of lead and warned of the danger it posed to human beings, especially children, and to the environment. The scientists were unable to stop the industrialists however, and the government allowed Ethyl to be marketed without restrictions. Leaded gasoline was the main means of propulsion of commercial and passenger vehicles in most countries in the world from the 1920s to the 1980s and 1990s.

The protean damaging results of Ethyl can only be estimated with imprecision. In 1988, an EPA study estimated that over the previous 60 years, 68 million American children suffered high toxic exposure to lead from leaded fuels. Some neurologists have speculated that the lead phase-out allowed average IQ levels to rise by several points, since one of lead’s effects is to stunt intellectual growth in children. Further, in every country on Earth, rates of violent crime decrease dramatically at around twenty years after the phase-out of leaded gasoline. The “lead-crime hypothesis” states that lead poisoning degrades the development of childhood brains in ways that increase aggression, reduce impulse control, and increase the chances of affected populations committing violent crimes in adulthood.

That twenty-year correlation between lead phase-out and a decrease in violent crime seems like something Dr. Alice Hamilton would be very interested in studying further were she alive today.

https://blogs.plos.org/speakeasyscience/2011/08/24/at-the-door-of-the-loony-gas-building/

Rick Wilson, D.M.D.